9. Mixed problems¶

Note

This section is the mastery exercise for this module. This exercise is explicitly intended to test whether you can bring together what has been learned in the rest of the module in order to go beyond what has been covered in lectures and labs.

This exercise is not a part of the third year version of this module.

As an example of a mixed problem, we’ll consider the Stokes equations. In order to make the treatment of boundary conditions somewhat simpler, we’ll employ a slightly different formulation of the equation than was presented in Section 6 of the analysis part of the course. Rather than the symmetric gradient form of the equations, we employ the laplacian form:

Where \(u\) is the velocity, \(p\) is the pressure, \(\mu\) is the viscosity, and \(f\) is a vector-valued forcing term. We will consider two forms of boundary condition. First, Dirichlet conditions on the velocity:

for a given vector-valued function of space \(g\). This can be used to impose zero slip conditions or a prescribed inflow. Second, the natural outflow condition:

The weak form of this equation is find \((u,p)\in V\times Q\) such that:

where

and where \(V_0\) is the subspace of \(H^1(\Omega)^d\) for which all components vanish on \(\Gamma\). The outflow condition is the “do nothing” condition which is imposed simply by not including the surface terms created by integrating the velocity equation by parts when formulating the weak form.

These equations are well posed so long as \(\Gamma\setminus \Gamma_D \neq \emptyset\). That is to say, there must be some outflow boundary. If \(\Gamma =\Gamma_D\) then there will be a null space comprising all of the constant pressure functions. We will implement the two-dimensional case (\(d=2\)) and, for simplicity, we will assume \(\mu=1\).

The colon (\(:\)) indicates an inner product so:

In choosing a finite element subspace of \(V \times Q\) we will similarly choose a simpler to implement, yet still stable, space than was chosen in Analysis Section 6. The space we will use is the lowest order Taylor-Hood space [TH73]. This has:

i.e. quadratic velocity and linear pressure on each cell. We note that \(Q^h\in H^1(\Omega)\) but since \(H^1(\Omega) \subset L^2(\Omega)\), this is not itself a problem. We will impose further constraints on the spaces in the form of Dirichlet boundary conditions to ensure that the solutions found are in fact in \(V \times Q\).

In addition to the finite element functionality we have already implemented, there are two further challenges we need to address. First, the implementation of the vector-valued space \(P2(\Omega)^2\) and second, the implementation of functions and matrices defined over the mixed space \(V^h \times Q^h\).

9.1. Vector-valued finite elements¶

Consider the local representation of \(P2(\Omega)^2\) on one element. The scalar \(P2\) element on one triangle has 6 nodes, one at each vertex and one at each edge. If we write \(\{\Phi_i\}_{i=0}^{5}\) for the scalar basis, then a basis \(\{\mathbf{\Phi}_i\}_{i=0}^{11}\) for the vector-valued space is given by:

where \(//\) is the integer division operator, \(\%\) is the modulus operator, and \({\mathbf{e}_0, \mathbf{e}_1}\) is the standard basis for \(\mathbb{R}^2\). That is to say, we interleave \(x\) and \(y\) component basis functions.

Fig. 9.1 The local numbering of vector degrees of freedom.¶

We can practically implement vector function spaces by implementing a new class

fe_utils.finite_elements.VectorFiniteElement. The constructor

(__init__()) of this new class should take a

FiniteElement and construct the

corresponding vector element. For current purposes we can assume that the

vector element will always have a vector dimension equal to the element

geometric and topological dimension (i.e. 2 if the element is defined on a

triangle). We’ll refer to this dimension as \(d\).

9.1.1. Implementing VectorFiniteElement¶

VectorFiniteElement needs to implement as far as possible the same

interface as FiniteElement. Let’s think

about how to do that.

cell,degreeSame as for the input

FiniteElement.entity_nodesThere will be twice as many nodes, and the node ordering is such that each node is replaced by a \(d\)-tuple. For example the scalar triangle P1 entity-node list is:

{ 0 : {0 : [0], 1 : [1], 2 : [2]}, 1 : {0 : [], 1 : [], 2 : []}, 2 : {0 : []} }

The vector version is achieved by looping over the scalar version and returning a mapping with the pair \(2n, 2(n+1)\) in place of node \(n\):

{ 0 : {0 : [0, 1], 1 : [2, 3], 2 : [4, 5]}, 1 : {0 : [], 1 : [], 2 : []}, 2 : {0 : []} }

nodes_per_entity:Each entry will be \(d\) times that on the input

FiniteElement.

9.1.2. Tabulation¶

In order to tabulate the element, we can use (9.6). We first

call the tabulate method from the input

FiniteElement, and we use this and

(9.6) to produce the array to return. Notice that the array

will both have a basis functions dimension which is \(d\) times longer than the

input element, and will also have an extra dimension to account for the

multiplication by \(\mathbf{e}_{i\,\%\,d}\). This means that the tabulation array

with grad=False will now be rank 3, and that with grad=True

will be rank 4. Make sure you keep track of which rank is which!

The VectorFiniteElement will need to keep a reference to the

input FiniteElement in order to facilitate

tabulation.

9.1.3. Nodes¶

Even though we didn’t need the nodes of the VectorFiniteElement to

construct its basis, we will need them to implement interpolation. In

Definition 2.44 we learned that

the nodes of a finite element are related to the corresponding nodal basis by:

From (9.6) and assuming, as we have throughout the course, that the scalar finite element has point evaluation nodes given by:

it follows that:

Hint

To see that this is the correct nodal basis, choose \(v=\mathbf{\Phi}_j\) in (9.9) and substitute (9.6) for \(\mathbf{\Phi}_j\).

This means that the correct VectorFiniteElement.nodes attribute is

the list of nodal points from the input

FiniteElement but with each point repeated

\(d\) times. It will also be necessary to add another attribute, perhaps

node_weights which is a rank 2 array whose \(i\)-th row is the correct

canonical basis vector to contract with the function value at the \(i\)-th node (\(\mathbf{e}_{i\,\%\,d}\)).

9.2. Vector-valued function spaces¶

Assuming we correctly implement VectorFiniteElement,

FunctionSpace should work out of the box.

In particular, the global numbering algorithm only depends on having a correct

local numbering so this should work unaltered.

9.3. Functions in vector-valued spaces¶

The general form of a function in a vector-valued function space is:

That is to say, the basis functions are vector valued and their coefficients

are still scalar. This means that if the VectorFiniteElement had a

correct entity-node list then the core functionality of the existing

Function will automatically be correct. In

particular, the array of values will have the correct extent. However,

interpolation and plotting of vector valued fields will require some

adjustment.

9.3.1. Interpolating into vector-valued spaces¶

Since the form of the nodes of a VectorFiniteElement is different from

that of a scalar element, there will be some changes required in the

interpolate() method. Specifically:

self.values[fs.cell_nodes[c, :]] = [fn(x) for x in node_coords]

This line will need to take into account the dot product with the

canonical basis from (9.9), which you have implemented as

VectorFiniteElement.node_weights. This change will need to be made

conditional on the class of finite element passed in, so that the code doesn’t

break in the scalar element case.

9.3.2. Plotting functions in vector-valued spaces¶

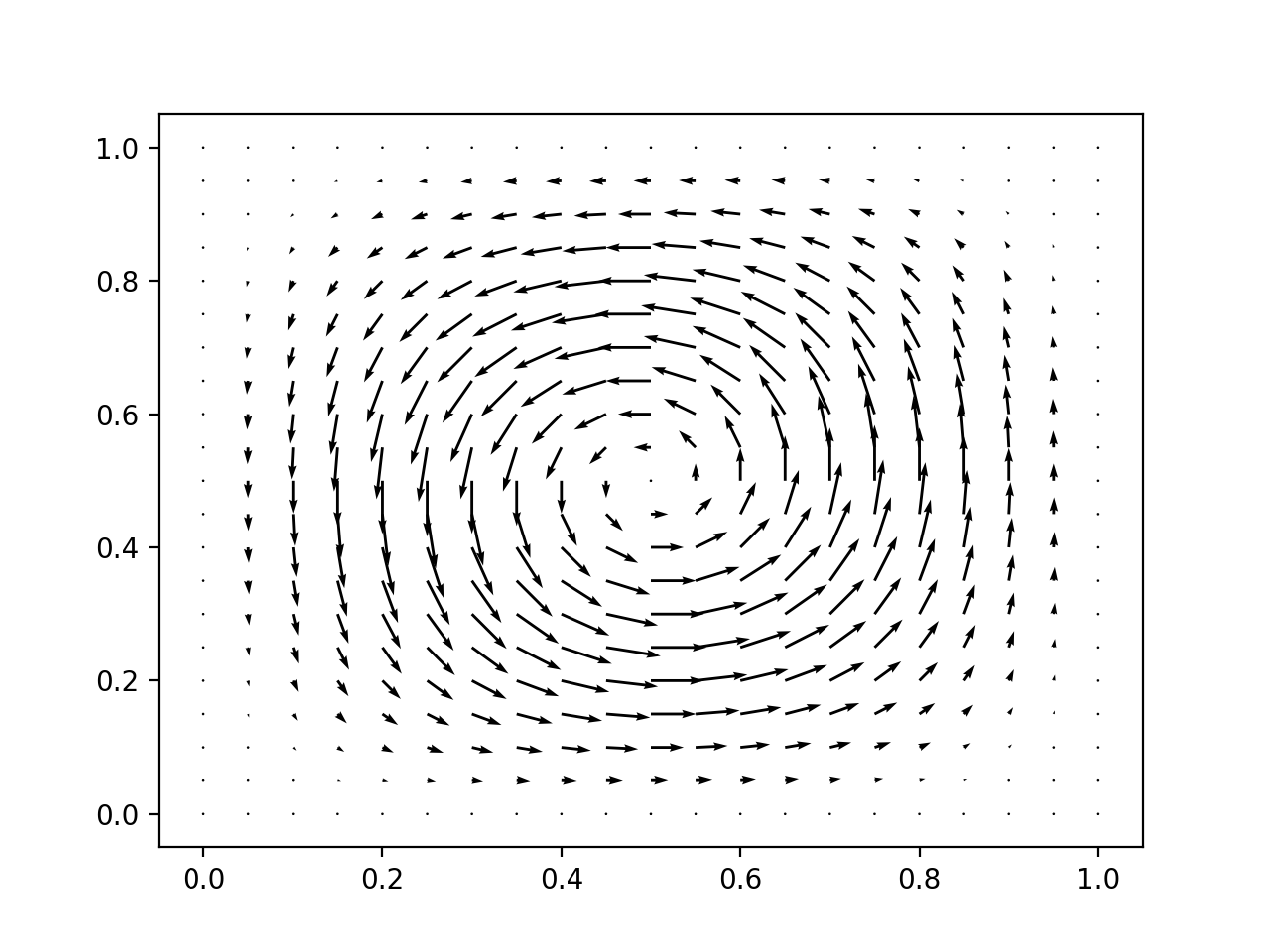

The coloured surface plots that we’ve used thus far for two-dimensional scalar functions don’t extend easily to vector quantities. Instead, a frequently used visualisation technique is the quiver plot. This draws a set of arrows representing the function value at a set of points. For our purposes, the nodes of the function space in question are a good choice of evaluation points. Listing 9.1 provides the code you will need. Notice that at line 3 we interpolated the function \(f(x)=x\) into the function space in order to obtain a list of the global coordinates of the node locations. At lines 6 and 7 we use what we know about the node ordering to recover vector values from the list of basis function coefficients.

plot() immediately after the

definition of fs.¶ 1if isinstance(fs.element, VectorFiniteElement):

2 coords = Function(fs)

3 coords.interpolate(lambda x: x)

4 fig = plt.figure()

5 ax = fig.add_subplot()

6 x = coords.values.reshape(-1, 2)

7 v = self.values.reshape(-1, 2)

8 plt.quiver(x[:, 0], x[:, 1], v[:, 0], v[:, 1])

9 plt.show()

10 return

Once this code has been inserted, then running the code in Listing 9.2 will result in a plot rather like Fig. 9.2.

1from fe_utils import *

2from math import cos, sin, pi

3

4se = LagrangeElement(ReferenceTriangle, 2)

5ve = VectorFiniteElement(se)

6m = UnitSquareMesh(10,10)

7fs = FunctionSpace(m, ve)

8f = Function(fs)

9f.interpolate(lambda x: (2*pi*(1 - cos(2*pi*x[0]))*sin(2*pi*x[1]),

10 -2*pi*(1 - cos(2*pi*x[1]))*sin(2*pi*x[0])))

11f.plot()

Fig. 9.2 The quiver plot resulting from Listing 9.2.¶

9.3.3. Solving vector-valued systems¶

Solving a finite element problem in a vector-valued space is essentially similar to the scalar problems you have already solved. It does, nonetheless, provide a useful check on the correctness of your code before adding in the additional complications of mixed systems. As a very simple example, consider computing vector-valued field which is the gradient of a known function. For some suitable finite element space \(V\subset H^1(\Omega)^2\) and \(f:\Omega\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), find \(u\in V\) such that:

If \(f\) is chosen such that \(\nabla f\in V\) then this projection is exact up to roundoff, and the following calculation should result in a good approximation to zero:

Note

The computations in this subsection are not required to complete the mastery exercise. They are, nonetheless, strongly recommended as a mechanism for checking your implementation thus far.

9.4. Mixed function spaces¶

The Stokes equations are defined over the mixed function space \(W = V \times Q\). Here “mixed” simply means that there are two solution variables, and therefore two solution spaces. Functions in \(W\) are pairs \((u, p)\) where \(u\in V\) and \(p\in Q\). If \(\{\phi_i\}_{i=0}^{m-1}\) is a basis for \(V\) and \(\{\psi_j\}_{j=0}^{n-1}\) then a basis for \(W\) is given by:

This in turn enables us to write \(w\in W\) in the form \(w=w_i\omega_i\) as we would expect for a function in a finite element space. The Cartesian product structure of the mixed space \(W\) means that the first \(m\) coefficients are simply the coefficients of the \(V\) basis functions, and the latter \(n\) coefficients correspond to the \(Q\) basis functions. This means that our full mixed finite element system is simply a linear system of block matrices and block vectors. If we disregard boundary conditions, including the pressure constraint, this system has the following form:

where:

This means that the assembly of the mixed problem comes down to the assembly of several finite operators of the form that we have already encountered. These then need to be assembled into the full block matrix and right hand side vector, before the system is solved and the resulting solution vector pulled appart and interpreted as the coefficients of \(u\) and \(p\). Observe in (9.15) that the order of the indices \(i\) and \(j\) is reversed on the right hand side of the equations. This reflects the differing conventions for matrix indices and bilinear form arguments, and is a source of unending confusion in this field.

9.4.1. Assembling block systems¶

The procedure for assembling the individual blocks of the block matrix and the block vectors is the one you are familiar with, but we will need to do something new to assemble the block structures. What is required differs slightly between the matrix and the vectors.

In the case of the vectors, then it is sufficient to know that a slice into a

numpy.ndarray returns a view on the same memory as the full vector.

This is most easily understood through an example:

In [1]: import numpy as np

In [2]: a = np.zeros(10)

In [3]: b = a[:5]

In [4]: b[2] = 1

In [5]: a

Out[5]: array([0., 0., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.])

This means that one can first create a full vector of length \(n+m\) and then slice it to create subvectors that can be used for assembly.

Conversely, scipy.sparse provides the bmat()

function which will stitch together a larger sparse matrix from blocks. In

order to have the full indexing options you are likely to want for imposing the

boundary conditions, you will probably want to specify that the resulting

matrix is in "lil" format.

9.4.2. Boundary conditions¶

The imposition of the constraint in \(V_0\) that solutions vanish on the boundary is a Dirichlet condition of the type that you have encountered before. Observe that the condition changes the test space, which affects whole rows of the block system, so you will want to impose the boundary condition after assembling the block matrix. You will also need to ensure that the constraint is applied to both the \(x\) and \(y\) components of the space.

9.4.3. Solving the matrix system¶

The block matrix system that you eventually produce will be larger than many of

those we have previously encountered, and will have non-zero entries further

from the diagonal. This can cause the matrix solver to become expensive in both

time and memory. Fortunately, scipy.sparse.linalg now incorporates an

interface to SuperLU,

which is a high-performance direct sparse solver. The recommended solution

strategy is therefore:

Convert your block matrix to

scipy.sparse.csc_matrix, which is the format that SuperLU requires.Factorise the matrix using

scipy.sparse.linalg.splu().Use the resulting

SuperLUobject to finally solve the system.

9.4.4. Computing the error¶

We will wish to compute the convergence of our solution in the \(L^2\) norm. For \(w\in W\), this is given by:

When we expand this in terms of the basis of \(W\), it will be useful to note that basis functions from the different component spaces are orthogonal. That is to say:

The direct result of this is that if \(w = (u, p)\) then:

9.5. Plane Poiseuille flow¶

One scenario for which the Stokes equations have a unique solution is plane Poiseuille flow. In this scenario, the domain is a rectangle whose upper and lower boundaries are no-slip (i.e. velocity zero). The right hand boundary is an outflow and the left hand boundary is a prescribed (Dirichlet) parabolic inflow which is zero at the top and bottom and maximal at the midpoint.

We can rescale the problem so that the domain is a unit square, in which case the boundary conditions are:

the constant \(c\) is arbitrary.

Fig. 9.3 Schematic of boundary conditions for plane Poiseuille flow.¶

It is straightforward to show that the velocity part of this solution is:

and that the pressure part is a linear function of \(x\).

Hint

When checking the correctness of the Poiseuille solution, don’t forget to check that the solution satisfies the outflow boundary condition.

9.6. Manufacturing a solution to the Stokes equations¶

Because the Poiseuille flow solution is quadratic in \(u\) and linear in \(p\), it actually lies exactly in the finite element space, so we expect the numerical finite element solution to be exact up to roundoff error. This sounds convenient, but actually it means that this scenario is not a very extensive test of an implementation.

The simplest modification to this scenario which avoids this difficulty is to choose a different solution function for \(u\) still of the form:

but with \(h(y)\) not quadratic, so that it does not lie exactly in the finite element space. This form of solution ensures that \(\nabla\cdot u = 0\) and that the outflow boundary condition can be satisfied. It will be necessary to modify the Dirichlet conditions to conform to the chosen solution. As before, the forcing term \(f\) is computed using the method of manufactured solutions.

9.7. Implementing the Stokes problem¶

The goal of this exercise is to implement a solver for the Stokes

equations, on a unit square. Implement

solve_mastery() so that it solves

(9.2) for a forcing function and boundary conditions

manufactured as described in section Manufacturing a solution to the Stokes equations.

Your full solution should:

Implement

VectorFiniteElement.Make the consequential changes to

Functionto enable values to be interpolated into vector-valued functions, and to create quiver plots.Assemble and solve the required mixed system for your chosen manufactured solution to the Stokes equation.

Compute the \(L^2\) error of the mixed solution from the analytic solution.

A convergence test for your code is provided in

test/test_13_mastery_convergence.py. In order to be compatible with

this code, your implementation of

solve_mastery() should return its results

as a tuple of the form (u, p), error.